The year was 1970. Peyton Simpson, a 45 year-old engineer and self-described “tinkerer,” was wrapping up a few loose ends of a business venture that had run its course. It was just after sundown when he first noticed thick black smoke rising into the night sky from behind a warehouse building across the street. “Fire,” he thought and he quickly jumped from his chair and ran to warn his neighbor. Entering the front door wide-eyed, excited and out of breath, he startled several men standing in the reception area. “I think you have a fire,” he exclaimed, “out back, there’s smoke behind your building!”

The year was 1970. Peyton Simpson, a 45 year-old engineer and self-described “tinkerer,” was wrapping up a few loose ends of a business venture that had run its course. It was just after sundown when he first noticed thick black smoke rising into the night sky from behind a warehouse building across the street. “Fire,” he thought and he quickly jumped from his chair and ran to warn his neighbor. Entering the front door wide-eyed, excited and out of breath, he startled several men standing in the reception area. “I think you have a fire,” he exclaimed, “out back, there’s smoke behind your building!”

Motionless and confused at first, one of the men soon recognized Peyton as his neighbor across the street and he quickly responded, nervously stuttering, “Oh no, no, it’s not, uh, not what you think. Here, come… come with me.” Peyton, was quickly escorted from the office through a small manufacturing area and warehouse to a graveled parking lot behind the building. There, he discovered the source of the smoke. Workers were tossing dirty and corroded electric motors and other metal parts into a blazing 55 gallon fire pit. Peyton immediately recognized what was going on: it was a common practice in those days. They were “burning off” the grease and sludge on old motors in order to rebuild and reclaim them for further use. The obvious unease and nervousness of the company’s workers and executives was also revealed: The Clean Air Act of 1970. What they were doing was illegal. That’s why they were doing it at night. If caught they could be prosecuted and even put out of business.

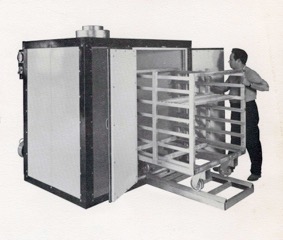

After some inquiring chit-chat, Peyton asked, “If I can show you how you can reclaim your old motors safely without smoke and pollution, would you be interested?” The answer was an enthusiastic yes and the rest is history. A few months after that fateful evening, Peyton Simpson delivered his first pyrolytic cleaning oven.

Within a decade, Pollution Control Products Co. would build a thousand more furnaces for other electric motor rebuilders, and over the decades after that, thousands more for all kinds of manufacturing applications, from Mom and Pops to Fortune 500 companies. His “tinkering” and inquisitiveness would open up many new markets in the U.S. and abroad making his company the largest manufacturer of “burn-off’ ovens in the world.